Active Electrical Cable (AEC) Fundamentals

AECs in AI Data Centers: The Full Stack Deep Dive from Physics to Procurement | CRDO, APH, ALAB, MRVL, AVGO

Active Electrical Cables (AECs) are a critical building block in modern data-center networking. An AEC is essentially a copper cable with active electronics - retimers - integrated at the cable ends. Retimers condition, equalize, and regenerate electrical signals, enabling them to travel longer distances and with higher reliability than passive solutions like DAC (Direct Attach Cables).

Today, we take a comprehensive deep dive into the AEC market in data centers. Over the course of this article, you will gain a clear understanding of the following topics:

Key concepts: retimer chips, reach & latency of AECs…

Bill-of-material (BOM) analysis of an AEC cable

AEC vendor qualification process with hyperscalers

AEC’s comparisons with optical modules

Shipment volume of 400G/ 800G AECs in 2025 and volume forecast for 2026

How to estimate future AEC volume based on XPU installment and network architecture

Pricing mechanism of AEC vendors

Pricing trend of 400G/ 800G AECs

The development and production progress of next-generation 1.6T AECs

Key players in the AEC market (include Credo, Amphenol, Astera Labs, Recodeal, Marvell, Broadcom…)

How major AEC vendors compare in 3 core competition criteria

Each hyperscaler’s procurement situation of AECs: procurement volume & pricing, key vendors & their wallet share, relevant clusters & networking architectures…

Section 1: The Basics - Understanding AEC

One important clarification is that AEC is not the only copper cable type with embedded active silicon - ACC (Active Copper Cable) also integrates chips (redrivers) in its cable ends. The key difference is that redrivers only amplify the analog waveform rather than reconstructing it. By contrast, AEC uses integrated SerDes and clock-and-data recovery (CDR) to fully recover and regenerate the data stream, thus providing stronger and more reliable signal quality. Today, the most advanced retimers in production are on 5 nm process nodes and are used in 800G AECs.

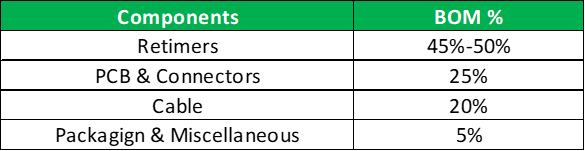

Retimers typically account for 45–50% of the total Bill-of-Materials (BOM) of an AEC cable. Note that one cable usually integrates two retimer chips, one at each end, both capable of managing multiple lanes simultaneously due to its parallel SerDes design (for example, an 800G AEC usually consists of eight 100G lanes). Our channel checks indicate a 400G retimer chip typically costs ~$15, while an 800G one is at roughly double the price now.

Apart from the retimers, PCB, together with connectors that physically connect the cable to the switch or compute tray ports account for ~25% of the BOM. While connectors are not hard to produce, reliability is critical to achieving the overall high reliability of AECs. Lastly, the cable itself represents about 20% of the BOM, with the remaining 5% attributable to packaging and other miscellaneous materials.

Reach: The achievable reach of AECs can be up to 7-9 meters at 800G speed. In practice, however, many deployed AECs are much shorter in length - typically 2-3 meters - because their use cases do not require 7-to-9-meter-long connections.

Shorter cables have the advantages of being cheaper, thinner and lighter. At 800G, a 7-meter AEC typically requires a 24-26 AWG, whereas a 3-meter one can use a thinner 28-30 AWG conductor (a higher AWG number corresponds to a thinner wire). The thinness and light weight of cables are important in modern AI data center deployments because they improve heat dissipation and make it easier to route and manage hundreds/ thousands of cables within confined spaces.

Latency: AECs can operate in both InfiniBand and Ethernet environments. The retimer chip adds roughly 1-200 nanoseconds of latency to the cable. With two retimer chips on both ends, the total added latency amounts to about 300 nanoseconds. However, because most AECs today are deployed in Ethernet scale-out environments where ultra-low latency is not the most critical consideration, such latency has generally not been majorly concerning.

Qualification process: To supply AECs to a major customer (typically CSPs), a vendor usually needs to go through a 6-9-month qualification process. During the process, the vendor needs to pass multiple stages, including unit-level tests, system-level tests, and limited-scale pilot deployments to test how its products interop with other components of the client’s network. This lengthy and resource-intensive process creates a competitive moat for leading suppliers, as customers are generally willing to dedicate qualification time and engineering effort to only a small number of potential candidates.

Comparison with optical modules: The main advantage of AECs over optical modules is reliability. Based on industry feedback, the probability of an optical module failing within the first six months of deployment is roughly 1 in 1 thousand, whereas that for AEC is closer to 1 in 100 thousand, a two-orders-of-magnitude difference. A higher failure rate becomes especially costly during AI training runs - when a link breaks, workloads often need to be rolled back to the earlier checkpoint, which can translate into millions of dollars of additional costs. Another key advantage of AEC is lower power consumption - AEC typically consumes 30% less power than optical modules at the same speed.

Section 2: AEC Volume and Market Model

Based on our checks, we estimate a total of 5 million Ethernet AEC cables sold in 2025, with the majority of volume concentrated at 400G/ 800G speeds. Looking ahead to 2026, we expect total AEC demand to roughly double to ~10 million units, with 800G AECs becoming the dominant category.

One key question for investors is how to estimate the number of AEC cables. To do this, the first step is to understand how AECs are actually deployed. There’re two general scenarios for scale out and front-end networks:

First-layer network: connect XPUs to Top-of-Rack (ToR)/ leaf switches, which represents the most common AEC use case

Upper-layer network: links between leaf and spine layers, spine and core layers, or both. These connections typically require longer cable lengths as they are usually cross-rack links

In the first layer scenario, the AEC-to-XPU ratio is relatively straightforward to estimate and is basically determined by the XPU’s back-end scale-out (or front-end) bandwidth. For example, in GB200 NVL72, each Blackwell GPU is given 400G of scale-out bandwidth, thus corresponding to 400G AEC per chip at the first-layer. By contrast, GB300 NVL72 supports 800G of scale-out bandwidth per GPU, implying either one 800G AEC or two 400G AECs for the first layer. Beyond this first layer, higher-level network connections are generally implemented using optical modules.

In the upper-layer scenario, the analysis becomes more nuanced. For back-end scale-out networks, traffic is typically all-to-all, meaning that data from the first layer must be fully carried into the upper layers. This implies that the total number of AECs required at each of the upper layers should be the same as that of the first layer.

Front-end networks, however, are usually designed with oversubscription, so not all traffic is forwarded upstream. For example, with a 3:1 oversubscription ratio at the leaf layer, the number of AECs required between the leaf and spine layers would be one-third of those used between the GPUs and the leaf switches. Because oversubscription ratios and topologies vary widely across front-end deployments, AEC estimates for upper-layers should be derived case by case, based on the specific oversubscription assumptions.

Apart from back-end and front-end networks, AECs can also be used in scale-up networks. However, this use case is even more complex, and since it has not yet been meaningfully deployed in practice, I will defer a detailed discussion to a future piece.

Now, let’s try to estimate the total volume opportunities for AECs. I compiled a list of XPUs expected to have the greatest impact on 2026 AEC volumes (including B300, GB300 NVL, R200, VR200 NVL, TPU v7, TPU v8, Trainium 2e, Trainium 3, and R300). For each platform, I estimated first-layer demand by multiplying projected XPU volumes by the corresponding first-layer AEC-to-XPU ratios.

This results in an implied first-layer scale out requirement of roughly 10 million 800G AECs or optical modules, or ~20 million 400G AECs/ optical modules. However, we also need to account for additional XPUs not included in this list, and thus we assume that total volumes to be ~50% higher, bringing the figures to 15 million 800G units or 30 million 400G units. As noted earlier, current market forecasts point to about 10 million total AEC units in 2026, and I will leave it to readers to judge for themselves whether that forecast appears reasonable.

For more detail on the underlying calculations and assumptions behind these figures, please DM me.

Section 3: AEC Pricing

Before getting into the specific pricing levels of 400G/ 800G AECs, I’d like to first address a more fundamental question - How do AEC vendors actually set their prices?

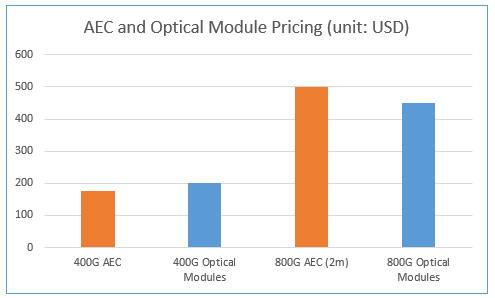

Many assume that a cost-plus pricing method would be reasonable for such a hardware, mass-production-driven industry. However, based on our discussion with AEC companies, pricing in this market is more a value-based approach - leading players such as Credo benchmark their AEC pricing against optical modules at the same speed. The logic is that in short-reach use cases, AEC can deliver comparable and maybe even better results than transceivers, with ~30% lower power consumption and much better reliability (as discussed above). As a result, AECs are priced slightly lower than same-speed optical modules. We think this approach is well-judged and allows AEC vendors to capture more value and margin than they would under a traditional cost-plus framework commonly used by hardware manufacturers.

Let’s look at some concrete examples. In 2025, 400G AECs are typically priced in the $150-200 range, compared with ~$200 for 400G optical modules. Looking ahead to 2026, we expect 400G AEC pricing to trend lower. For example, Credo has already supplied close to 1 million units of 400G AECs to AWS, and as volumes move to such a scale, AWS should be able to negotiate lower prices on incremental orders.

800G AECs have also been sold at elevated prices so far as the product is still in the early ramp-up phase. A 2-meter 800G AEC can cost around $500 even for hyperscale customers such as AWS and xAI, while longer-reach SKUs (5 meters and above) and Y-cable configurations (one 800G fanning out into two 400G ports) are typically priced at $600 or more. In comparison, single mode 800G optical modules are sold at around $5-600 and multi-mode modules are sold at below $400 in 2025. The elevated price points of 800G AECs reflect early-stage supply constraints, combined with strong and urgent demand from multiple hyperscalers for 800G AECs.

Section 4: The Next-Generation 1.6T AECs

AEC vendors have been advancing their designs for the next-generation 1.6T AECs. Current expectations point to an initial rollout around Q2 2026, followed by broader adoption in late 2026. The primary technical bottleneck now lies in 224G-per-lane copper cable manufacturing (compared to the 112G-per-lane cables used for 400G/ 800G AECs), where production depends heavily on specialized German equipment which faces long lead times. Beyond technology hurdles, 1.6T AEC adoption also needs to align with next-gen chip launches. One of the most natural early use cases would be Nvidia’s Vera Rubin chips that come with 1.6T scale-out requirement per GPU.

1.6T AECs are expected to rely on 3nm retimer silicon, which is currently manufacturable at scale only by TSMC and Samsung. Marvell appears to be slightly ahead in bringing 3nm retimers to maturity, while Credo is close behind and still has runway until mid-2026 ahead of the mass-production cycle. With the current generation of retimer chips, 1.6T AECs can reach sub-3-meter transmission distance. Extending connectivity to 7 meters or above, comparable to today’s 800G AECs, would require more advanced next-generation retimer silicon.

Section 5: Key Players in AEC Market

There are broadly two types of AEC vendors. The first category is vertically integrated providers - they design and produce their own retimer chips while also developing and supplying the complete cable assemblies, with Credo as the most representative example. The second category designs the cable solution but sources core retimer chips from third-party designers like Marvell and Broadcom, operating more as a system integrator. Below is a breakdown of the key players in each category.

Type 1: Vertically Integrated Providers

Credo (CRDO): The company is the incumbent in the Ethernet AEC market with dominant shares previously. The company’s technological foundation lies in its SerDes design, which it subsequently extended into AEC retimer chips and DSPs. For 800G AEC retimers, the company offers both 12nm and 5nm options. The more mature 12nm retimer carries higher power consumption (10W vs. 7W for the 5nm version) but is meaningfully cheaper.

As a vertically integrated provider, Credo designs the entire AEC solution in-house and outsources manufacturing based on its proprietary designs. To date, its primary manufacturing partner has been BizLink, but the company is also evaluating the addition of a second production partner - Foxlink - to help handle increasing orders in 2026/ 27.

Astera Labs (ALAB): I wouldn’t characterize Astera as a pure vertically integrated solution provider. It does design and produce retimer chips in-house, similar to Credo, but it often supplies these chips in the form of paddle cards to downstream assemblers or solution vendors. Astera’s current retimer chips are built on 12nm process nodes, whereas competitors such as Credo and Marvell already offer 5nm solutions for 800G. As a newer entrant to the market, Astera has also demonstrated a willingness to price its products below peers like Credo in order to gain market share.

Type 2: System Integrators

Recodeal (688800.CH): The company runs its AEC business through a joint venture with Innolight (300308.CH), in which Recodeal holds a 70% equity stake. Under the arrangement, Recodeal is primarily responsible for product design and manufacturing, while Innolight contributes its established relationships and sales capabilities with U.S. hyperscalers.

Manufacturing and assembly of the JV is done in the U.S./ Mexico and Thailand. The U.S. facilities serve as the main base, where capacity previously allocated to other businesses (like auto) has been repurposed for AEC production; the Thailand operation is a greenfield expansion. The company’s key competitive advantage lies in its cost structure and pricing, which we discuss in more detail in the following section.

Amphenol (APH): The company designs and delivers the complete AEC assembly while sourcing retimer silicon from partners (especially Marvell). It then optimizes the full cable at the system level for signal integrity, thermals, mechanical reliability, and large-scale deployment in AI clusters. Amphenol’s advantage is deep customer relationships and global manufacturing capacity that can support high-volume ramps across regions.

TE Connectivity (TE): Very similar to Amphenol

Eoptolink (300502.CH): The leading optical module vendor is also exploring opportunities to participate in the adjacent AEC market. The company sources retimer chips from both Broadcom and Marvell, but with a heavier weighting to Broadcom due to their close relationships.

Broadex (300548.CH): The company produces and sells AECs through its subsidiary EverPro. It has close relationships with Marvell and is expected to rely heavily on Marvell retimer chips in its AEC shipments. One of Broadex’s key customers is Google, which is seeking to replace some of the DACs used in its 3D Torus architecture with AECs to improve interconnectivity.

Part 6: Competitive Landscape

Which AEC vendors are best positioned to gain share in the highly competitive 2026-2027 cycle? To address this, I compare the key players across three core dimensions that ultimately determine their competitive strength:

1) Retimer Chips

Credo is widely recognized for its top notch analog mixed-signal circuit design capabilities. The company also benefits from in-house chip development, which provides greater design flexibility and tighter integration with other components in its AEC solutions. Based on our checks, Credo’s chips appear advantageous on power efficiency and signal interference resistance, delivering slightly better signal integrity than Marvell’s.

Marvell also has a strong SerDes IP. Its retimer chips are the most widely adopted by AEC system integrators (more than Broadcom’s). The company has a large R&D organization, which shall have helped it progress ahead of Credo in terms of 1.6T AEC retimer development. Additionally, we heard that Marvell’s retimers are typically priced 15-20% below Credo’s when supplied to third-party buyers.

However, for a system integrator, chip performance is inseparable from system-level integration. Beyond the capabilities of the retimer itself, the integrator must also ensure it interfaces and operates well with all other components in the full assembly, so that the chip’s performance can be fully realized in the end system.

Astera Labs’ AEC retimer capabilities are derived from its legacy PCIe retimer technology. The company has strong chip design expertise, and its use of the 12nm process node helps keep production costs relatively low.

2) Mass Production Capability

Among all vendors, Credo has most clearly demonstrated reliable, large-scale AEC production capability, having been the only supplier to deliver millions of high-speed AECs prior to 2025. Its strong execution with customers such as AWS and Microsoft has earned it credibility and helped it secure major 800G AEC orders from customers like xAI.

Another key advantage is Credo’s vertical integration. As a full-solution provider with all designs developed in-house, Credo can diagnose and resolve product issues for customers much more quickly. In contrast, when Amphenol receives client requests, it must coordinate with Marvell on retimer-related issues, which lengthens the issue-resolution cycle.

3) Prices

Due to the value-based framework we revealed previously, AEC pricing across vendors is driven primarily by corporate strategy rather than underlying cost structures. Credo and Amphenol often command premium price points relative to peers according to their market positions. Recodeal, by contrast, is willing to operate at lower gross profit margins (GPM), typically in the 40-50% range, allowing it to gain some price advantages. By comparison, Credo’s Product Sales segment, which encompasses its AEC business, reported a 63% gross margin in 2025. Astera Labs’ AEC pricing also sits toward the lower end of the spectrum.

Part 7: Customers

The primary buyers of AEC cables are hyperscalers. In the final section of the article, I will dive into how each hyperscaler approaches AEC procurement, with specific details on their:

400G/ 800G AEC procurement volume

Main AEC vendors and their rough wallet shares

XPUs and clusters that use AECs

The hyperscalers covered in this section include Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Meta, xAI, and Oracle.